MVT Celebrates Black History Month

Friday February 3, 2023

Throughout the month of February, we will be posting ways you can celebrate Black History Month around Mount Vernon Triangle – stay tuned for more in our ongoing celebration of Black History Month!

Learn About the Evolution of African-American Religious Music with Bible Way Church

(2/2/23) In celebration of Black History Month, Bible Way Church is hosting the four-part series – “I hear Music in the Air: The Evolution of African-American Religious Music” – virtually on Zoom every Wednesday evening in February at 7pm. Discussion next Wednesday, February 8 will focus on Gospel Music Pioneers while Gospel Music Aggregations & Bible Way Church Music History will be the topics on February 15 & 22, respectfully.

Established in 1928, Bible Way Church joins Second Baptist (established 1848 prior to the Civil War) and Mount Carmel Baptist Church (established 1876 just after the Civil War) as Mount Vernon Triangle’s three historically significant churches that have provided a combined 417 years of spiritual and civic service to MVT and the District of Columbia. Read this past Triangle Times article to learn more about our community’s spiritual foundations!

Bringing Real History to Real Life in Prather’s Alley

(2/9/23) In celebration of Black History Month we are introducing a multi-week series that will take a look at the historical and cultural significance of Prather’s Alley. Today, Prather’s Alley is a popular and critical component of Mount Vernon Triangle’s transportation infrastructure network. However, it also is a place of great historical significance. The alley and its adjoining buildings were once central to life for Mount Vernon Triangle’s African-American community.

In next week’s Triangle Times, we will further explore this place that the 11 African American families called home before the turn of the 20th century as well as look more broadly at the historical impacts of alley-dwellings across DC. This will be followed by an interview with the design firm, EL Studio, which worked with MVT CID to bring this story to life with the newest art installation adorning the alley.

Please join us as we rediscover this important throughline connecting Mount Vernon Triangle’s rich past, vibrant present, and equally exciting future!

Meet the Residents of Prather’s Alley’s Past

(2/16/23) In this installment of our MVT Black History Month celebration, we sat down with Kim Williams who is a Historic Preservation Specialist & National Register Coordinator at the DC Office of Planning to learn more about the 11 African American families who called Prather’s Alley home before the turn of the 20th century. Ms. Williams was the lead researcher on “The DC Historic Alley Building Survey” published by DC Office of Planning in 2014 as well as the author of “The Surviving Cultural Landscape of Washington’s Alleys” published in the Historical Society of Washington D.C.’s Washington History Fall 2015 edition.

For this interview, Kim looked at the the 1900 U.S. census to uncover some fascinating truths about the people living in Prather’s Alley. Read the interview below:

MVT CID: Can you provide us with any additional information about the 11 African American families who lived in Prather’s Alley at the turn of the 20th Century?

Kim Williams: Based upon the 1900 U.S. Census, all eleven families living in Prather’s Alley were working-class Blacks all of whom were renters. The family structures vary from smallish households with a husband/wife couple, to one family consisting of a husband/wife and eight children. Two households were headed by women (one widow and one unmarried) and several households had a lodger living with them. The male heads of household were typically laborers, one janitor and a couple of drivers, and the women worked as laundresses or domestics. Half of the residents could read and write, the other half were illiterate. In the case of the single female head, she was 27 years old and lived with three children listed as her three sisters (ages 9, 6, and 2). She was literate, worked as a laundress, and had a female laundress, also a laundress.

MVT CID: More generally, why did so many black families make their homes in DC alleys during this time?

Kim Williams: Many Blacks found housing in the alleyways for several reasons. There was a shortage of housing, in general, but especially for lower-income and Black residents. Alley dwellings were more affordable as the rents were less than street-facing houses, so alley dwellings were the only lodgings available. While many lower-income whites started out in the alleys, they were able to move up and out of the alleys over time. Blacks often could not because of racial discrimination in both the job and housing markets that prevented that movement out of the alleys and into street-facing housing.

MVT CID: Can you describe the conditions of the alleys and a typical alley dwelling?

Kim Williams: Alley houses in DC were small dwellings—often just twelve feet wide—with two small rooms on the first floor and two on the second and no indoor plumbing or heat. Residents relied on water pumps in the alleys and on outhouses in their tiny backyards. The kitchens were in tiny lean-to sheds at the rear of the alley dwellings. The alleys themselves were busy places with a variety of buildings and uses from the alley dwellings to commercial operations. In the case of Prather’s Alley, the alley was home to the 11 households, a bakery complex, a bottling plant, several stables, a blacksmith shop and warehouses. Given those uses, the proximity to horses and their manure, poor sanitation in the alleys, and neglect by the city in terms of cleaning up and maintaining the alleys, the alleys were often unhealthy places to live. Still, by virtue of the fact that alley residents lived in close quarters, they all knew one another, often worked and played together, and looked after one another. So, they were tight-knit communities, not necessarily found on the streets.

MVT CID: What has happened to these alley dwellings – do any still exist in DC?

Kim Williams: The vast majority of the city’s alley dwellings were demolished during the mid-20th century. They were demolished both as part of government efforts to eradicate the city’s slums and through abandonment and replacement with garages and parking lots, etc. with the invention of the automobile. However, about 100 alley dwellings do still exist, mostly in Georgetown, Foggy Bottom and on Capitol Hill. These largely survived the government efforts to eliminate them as white professionals bought them up in the late 1940s and early 1950s, renovated them, and brought in electricity and plumbing. Those alley dwellings are still occupied, but by the upper income echelons and not the poorest segment of the city’s residents who originally occupied them.

MVT CID: Putting this discussion in the context of Black History Month, why do you think it is important to document and preserve the memories and stories of these alley dwellings?

Kim Williams: I think it’s important to remember the alleys as refuges for those poor and mostly Black residents who had no other housing options. The alleys were insanitary places to live due to the lack of services and negligence on the part of city (i.e. no infrastructure services, no trash pickup, rodent removal, etc.), but they also developed into close-knit communities. They were concealed from the public streets and closed to traffic, so residents used the alleys as their front yards and as common space to work, play and socialize. Alleys were often a sort of community within a community where Black residents lived in the interior of the squares and Whites occupied the street-facing houses surrounding them. They lived in close proximity but did not integrate in any way.

MVT CID: In your opinion, how can alleys and other public spaces promote diversity and inclusion today?

Kim Williams: This is a challenge. From a residential perspective, building new dwellings in the alleyways can be expensive, so even if they are small, they are not necessarily affordable and in that way not economically inclusive. Similarly renovating existing non-residential alley buildings, like former warehouses or stables, for residential or commercial purposes is also expensive. So the new uses tend to cater to a more upscale buyer or clientele which is also not always terribly diverse. Because these new uses and new buildings obscure the social history of alleys, I think any new development in the alleys should come with some public project (art or signage type thing) that interprets that alley’s history, honors those people and activities that existed there in the past, and offers some kind of experience that everyone can engage.

Thank you, Kim for taking the time to speak with us and shed light on this often-forgotten part of DC’s history!

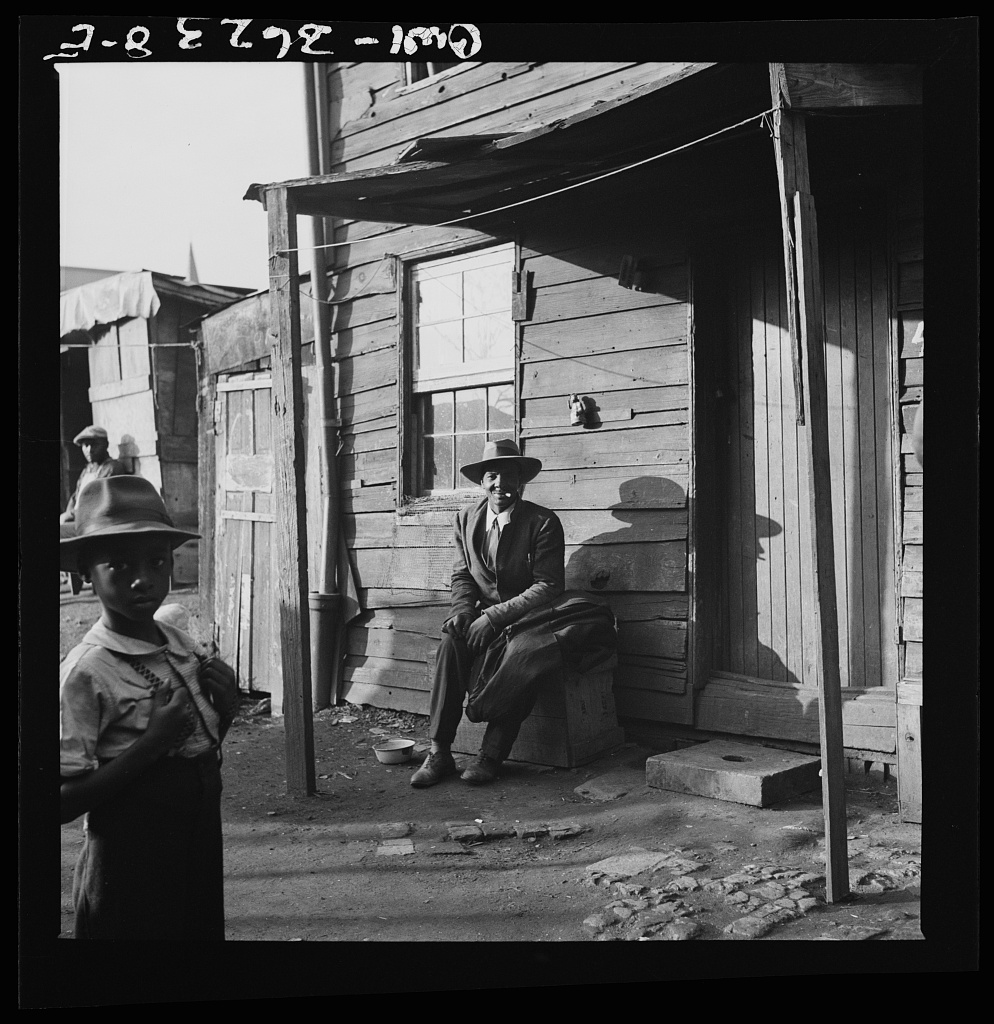

Examples of life in DC’s alley dwellings circa 1935. (All images sourced from the Library of Congress.)

MVT Celebration of Black History Month Concludes with More Events!

As our celebration of Black History Month comes to a close, we would like to spotlight a few more ways you can still celebrate with members of the MVT community:

Thursday, February 23

Bhakti Yoga

928 5th Street NW

Bhakti Yoga invites you to join their weekly free Satsang where this week they will be joined by Lori Perkins who will be leading a discussion on Spirituality & Black History. The program will begin at 6:45 pm and will be available to stream online or attend in-person.

Sunday, February 26

Mount Carmel Baptist Church

901 3rd Street NW

Join members of the Mount Carmel Baptist Church for a special Black History Program during Divine Worship Service on Sunday, February 22. All are welcome to attend either in person or online.

Bhakti Yoga

928 5th Street NW

Head back to Bhakti Yoga for their Donation Community-Based Class Honoring Black History Month. The 60-minute restorative vinyasa flow will be led by Maia Wise and will focus on the theme of “Comfortable with Uncertainty”. You can register for the class online with all the donation proceeds going to DC Justice Lab.